|

In beautiful Kerala in southern India now, and I happen to have a strong enough internet connection to edit this site. Will attempt to post a bit about the past month this week!

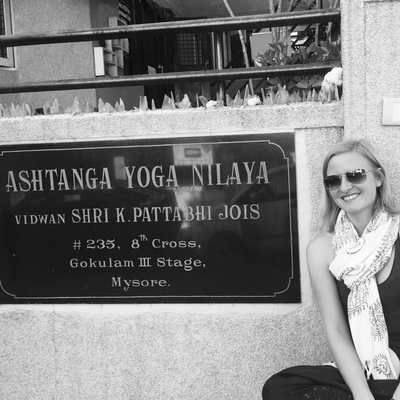

I was introduced to Ashtanga Yoga by Bobbi Boston in Los Angeles, and I was so fortunate to spend my first month in India practicing with Saraswathi at KPJAYI in Mysore. Here's a bit of what daily practice there was like. ... "One more," she yells from inside the shala. "One more. Come!" The window near the staircase is open just enough for the hushed sounds of breath to pass through, punctured by her sharp words. The student at the front of the line enters the shala, and we all shuffle up a step or two. From the outside, this building looks no different from the other homes in the neighborhood. The facade is neutral with brightly colored accents, and rot iron gates and railings wrap around the outside. However, it's the only home on the block with a dozen scooters and bikes parked outside and its own coconut vendor. Some days when the line winds down the staircase and students lean against the walls, it gets noisy with conversations just above a whisper. Together the many murmurs about day trips, the best taxi drivers, and nearby hotel pools are enough to drown out her voice. "Come, one more!" Someone near the window hears the words pass through the sheer white curtain, and soon arms are waving and "one more" is whispered along the line like a game of telephone. When the next student finally startles and presses the door open, there's enough open air for all of us to hear: "Quickly! You talk after!" To an outsider her words might seem aggressive, but it's only her love of the practice that makes the words forceful. Saraswathi was taught by her father, Shri K. Pattabhi Jois, in the lineage of Krishnamacharya, and in India the lineage of a teacher and a practice is of the utmost importance. Jois said that the only people who can't practice Ashtanga Yoga are lazy people, and there is nothing lazy about her teaching. In the shala she commands the space with selflessness, devotion, and humor. Even in her 70's she moves with the strength and grace of someone half her age. She can hold one student's foot in a balancing pose, while also directing another student through the correct breath and movement of a sun salutation. And the next moment she's marching diagonally through the small space between each mat, eyes fixed on a new student, while exclaiming, "bhujadpidasana is not correct!" As yet another student rolls up his mat, she doesn't miss a beat. "One more!" In December, the line was short. Sometimes only few people clutching mats at the top of the stairs meant a five-minute wait. Now the line often reaches the bottom of the staircase, and I stand near the coconut vendor, envying the students who have finished their practice and moved on to drinking coconuts. On these days the wait is an hour. One day I turned to my neighbor and made a comment about how long the line was. Her face lit up, and she said, "I don't mind!" Behind her cheerful, carefree words were so many unsaid things. It was all she had to say to wake me up to my western mind. What's the rush? Do I have somewhere else to be? What's wrong with just standing here and doing nothing? The words "Happy Journey" are everywhere in India. Plastered on billboards at the airport, flashed across electronic signs at tolls on major roads, and printed on bus and train tickets. My Uber driver even said it as I exited his car the other day. I found the words a little cheesy at first. (And if I'm being perfectly honest, I tend to associate "journey" with the TV show The Bachelor, so maybe I'm the cheesy one.) But it is a lovely reminder from India that you better enjoy the process. The quickest way to make yourself miserable here is to rush or focus on the result. Some days just finding a working ATM might take a couple hours, so it's best to make it a pleasant walk along an unfamiliar path or have a chai along the way. Happy journey. And so it is with the line. Far from being an annoyance, it is part of the process. I watch the woman across the street effortlessly draw a beautiful mandala with chalk powder or rice flour outside her front gate. Her 3 children, in school uniforms, race out of the home and jump on a scooter with their father, playfully fighting over who will sit where. The local fruit and vegetable vendors ride their bikes down this dirt road with large trays balanced across the handlebars. These men shout their offerings with elongated vowels. Some days Saraswathi comes outside and shouts her order back over the balcony. She simply nods her head in approval as she watches the vendor weigh each item. Then she disappears back into the ocean of breath, and we all wait to hear her call for one more. We're all assigned practice times when we register. Between 4am and 10am. I thought I had lucked out when I saw 9am written on my student card, but that was before I knew that music from the temple next door to my apartment would wake me up at 5:15am every morning. I know the tune by heart now, and it has quite a lively beat for that hour of the day. It goes on for a half hour of melodic ups and downs. Unfortunately, the quality is what you might imagine playing a radio over the loudspeaker at Target would sound like. It used to alarm me, but now I tend to wake shortly before it begins, and the intro plays in my head in anticipation of the real thing. This, too, is part of the process. What was initially a disturbance, but that I now know I'll miss when I'm gone. Happy journey. Ashtanga Yoga is method that incorporates all 8-limbs of yoga and follows a set sequence of postures for the physical practice. There are led classes, which are similar to yoga classes in the west. But traditionally Ashtanga is taught Mysore-style, named after this very place where it started, in which the sequence is done individually in a room with other practitioners, a teacher, and sometimes assistants. Each student learns the postures at a pace dictated by his or her teacher, and this speaks to the importance of lineage. The practice is never diluted because it is only passed directly from teacher to student. The Ashtanga teacher I first practiced with in LA learned here in Mysore, and so has every other authorized or certified Ashtanga teacher. This sense of tradition has an eclectic mix of students from all over the world standing outside an otherwise typical home in the neighborhood of Gokulam waiting to hear two simple words. Near the shala door, shoes are neatly scattered. Taking off my shoes feels like a ritual. It's when I listen more intently because I like to open the door before she has to call twice. Following her words, the door creaks as I enter, and a puff of humidity presses through the cooler air outside. The breath and movement of three-dozen students heats the room. Saraswathi points toward the newly vacated space, and I assess the best path through the extended limbs and focused gazes. I lay my mat down, and then I make my way to the small changing room. Bags cover the floor, and they are mostly filled with the modest clothes we all wear outside over our leggings and tank tops. When I step onto my mat, the breath comes effortlessly. It's second nature to join; the sound pulls me in like a wave. It has a greater force here than anywhere else I've ever practiced. Perhaps because this is what we're all here for: to practice where the practice started. I get so lost in it one day that I don't hear the words directed at me. "Marichyasana D is wrong," Saraswathi says loudly from across the room. It takes her saying it twice for me to realize that I am, in fact, practicing Marichyasana D. There is magic in the way she says things like this because she manages to convey the importance without judgment. The emphasis behind her words is for the practice to be precise, to be experienced in full. I keep my hands clasped, but turn my head to make eye contact with her. "Straight! Sit up straight," she says with exasperation. She is not impressed by my hunched over twist, and neither is my spine. I adjust myself to sit taller, finding space and length where my lower back has gotten sleepy. It's enough to feel better, and it must look better because she has moved on to the next student, inquiring about which asana she just practiced. I accidentally ended up in my first yoga class in 2006. It was on a beach in Maui, and my dad and my brother ditched me mid-way through. This practice in Mysore is a world away in both location and intention. In some practices here I want to hold on, to remember every little moment because I sense how temporary it is. But after 10 years of practice that has hardly been linear, I try to remind myself that this is part of the process. It matters as much as that first practice and each one in between. A practice that is whole isn't one of perfect poses, but one of waiting and moving and asking questions and being reminded of bad habits and waking up your self. Happy journey. When I finish my practice, I gather my things and cover myself in looser clothing. I tip toe back through the tangled limbs, and my eyes search for Saraswathi to nod in gratitude. Here namaste only means hello, but there are other ways to acknowledge your practice and your teacher. She is busy moving a student's feet behind his head, but not too busy to notice that another student is about to roll up her mat. I catch her attention momentarily as she looks toward the door, and she nods with a quick smile. "One more!"

8 Comments

My mom has only subtly asked me when I'll write something, and I have tried. I have a dozen blog posts partially written because every time I start to write about one thing I suddenly want to write something else. So I open a new document, record a new thought, and as soon as I search for more words, I'm lost. It's the same way I felt walking around Mysore when I first arrived. One block is filled with beautiful homes and lush, old trees, and the next is slums with torn plastic tarps for shade. Then the following corner has a traditional restaurant that serves food on banana leafs, and across the street a cow is eating garbage. Another block over is a Domino's Pizza next to a Samsung store. Beggars stand near the bus stops on this main road, and children in school uniforms wait on benches, exchanging stories and laughs. A Mercedes drives by, and a small rickshaw filled with six people lurches over a speed bump and struggles to accelerate. Farther down is the neighborhood sweets shop, which also happens to be right next to the best food cart for churumuri, a favorite local snack of chopped fruits with spices and rice puffs. The smell of earthy spices and frying oil from other stands mixes in the air with exhaust from the nearby traffic. The modern grocery store on that same block is a one-stop shop for everything for flatware to underwear. Outside vendors with fruits and vegetables compete by offering lower prices. They measure the weight in balances, placing the produce on one side and a metal kilogram on the other to determine the correct amount. I have been to places like this before, where the extremes of life are so close together. But each one is unique. And each one wakes you up to all of (for lack of a better word) your shit: what you take for granted, what you avoid, what you attach to. My first week here I barely took any photos. As if my blonde hair and generally confused facial expression weren't enough to make me stand out, pulling out my camera made me feel even more foreign. And my eyes had enough to take in without adding a second lens. Just crossing the street felt like a task. I awkwardly waited, attempting to find the best moment to make it through oncoming rickshaws, scooters, cows, cars, and buses. I often watched dogs successfully cross the street with more grace and ease than I did. Three weeks later I now know that there is never a best moment, but the oddly magical thing is that you always make it across. Yes, drivers honk their horns, and buses don't mind coming within inches of your toes, but there is no perfect timing, so you just go. And everyone is in it together. Which might be the dorkiest thing I could say, but there's something about a little madness that forces you to see other people. Instead of staring at a red light and waiting for it to change, you stare at oncoming traffic and with the right number of beeps and a strange dance of speeding up and slowing down and compromising you figure out a way for everyone make it through. The dogs still look more agile than I do, but my eyes have adjusted. This week on my walk home from the shala someone pulled over and asked me for directions, so my face must look less unsure than it did when I first arrived. To my own surprise I even guided him in the right direction. Mysore has been a lovely little pocket of India to get my feet wet. I've fallen in love with the people, the food, and, of course, the YOGA. Admitting that I struggled with crossing the street here might elicit a laugh from a Mysorian because this is the quiet, calm part of India. Many people call this city a soft landing. At the advice of others students who studied yoga here, I arrived with a hotel booked for 3 nights and planned to spend my first full day wandering around looking for homestays and apartments. I started that morning wary of whether this plan would work, and by evening I had more accommodation options than I knew what to do with. Eventually I'll finish the half-written words about practicing yoga here, taking a Sanskrit class that's held in the women's locker room, the new floors at the shala, riding on a scooter with my 30-pound backpack, visiting a cotton factory, the rickshaw driver who renewed my faith in humanity, and finding a cockroach on my yoga mat. It would be foolish to think that 3 weeks or even 6 months is enough time to really figure anywhere out. I've lived in LA for 6 years, and I still don't have it figured out.

As I roamed around Mysore the other day, my mind still taking everything in, I thought about a quote from Winnie the Pooh. Sophisticated, I know. "Life is miserable," moaned Eeyore. But Pooh just laughed. "Oh, Eeyore! It's your mind that's miserable. Life is just life." I could say that India is beautiful, challenging, chaotic, vibrant, noisy, delicate, mysterious, overwhelming, generous... But India is just India. And my mind is trying to catch up. "Relax your arm. Relax your arm. Relax your arm." Each time the nurse becomes more adamant. My gaze stays down as she holds the first needle inches away from my apparently tense arm. I think I've relaxed it as much as I can, but there's always more room to let go. I hear her words again against loud Bollywood-style on-hold music, as I wait on the phone with the visa office and then a third-party. Relax. But I can't. Or I make the choice not to. On Monday I taught my last yoga class. When I come back in 6-or-so months that might seem like no big deal, but in the moment it felt like everything. And all day I couldn't relax. I held so tightly onto wanting everything to be perfect. Several weeks ago one of my friends told me he had a gift for me. He explained that he had made it at one of those pottery-painting places, and I could see the excitement in his eyes over its beauty. Last week when I saw him, his expression had changed. He told me it had come out looking a little differently than he had planned. As he handed me a bag with tissue paper carefully wrapped around the ceramic piece, he said that before it was fired in the kiln everyone had remarked on how perfectly it was going to turn out. With a little trepidation and a nervous smile, he said, "But..." As I pulled this Buddha out of the bag, I burst into laughter. The laughter was contagious, and soon others were admiring this piece of art. Tears rolled down my face as we all tried to come up with what to call this very special Buddha.

I thanked my friend and told him I wouldn't want this piece to look any other way. Over this past week I have cried many desperate, stress-filled tears over the ordeal of STILL waiting for my visa. And when I've needed a laugh? I glance across the room and see this Buddha. Because RELAX YOUR ARM. Let go. That shot is going right into the muscle whether you tense up or not. The third-party visa servicer is giving me the same news regardless of how many times I have to repeat myself between sobs. My friend could have spent more time painting, and the heat of the kiln might still have transformed his work in an unexpected way. In Sanskrit the word for heat is tapas, but it is also defined as discipline and the use of heat or fire or fierceness in your practice to yield transformation. Some days you show up on your mat and are transformed into holding a handstand, and some days you are transformed into crying in child's pose. Typically the level of change goes much deeper than what the pose looks like from the outside. And the challenge is to learn from the transformation, rather than dictating how you wanted it to turn out. Can you learn just as much from falling on your face as you do from staying in the pose? Pending the arrival of my visa in the next 72 hours, in December I'll be practicing yoga at an institute established by the late Shri K. Pattabhi Jois, which is now run by his daughter and grandson. He created Ashtanga Yoga, which is the yoga system that most modern athletic/power forms of yoga are based on. He was well known for saying: "Practice, and all is coming." For now this Buddha is going into storage, but it will live (amongst other Buddha's, mala beads, and crystals) next to my mat when I have a home yoga space again because this is the practice. Show up, do your work, and care deeply. But let go. Today I bought a backpack. I'm not by any stretch of the imagination a backpacker. But today I bought a backpack to use for 4-6 months in India, which I guess qualifies me as a backpacker. Or so that's what Andy at REI told me. When I looked bewildered at the sight of my new pack (as they call it), he reassured me, "In two months, you'll know this thing inside and out." Here's hoping. When I arrived at REI I made a beeline for the backpacks, quickly got freaked out, and headed to the clothing section instead. Eventually I got up the nerve to ask someone for help with the backpacks, and I half expected the salesclerk to take one look at me and laugh or fear for my survival. But Andy simply grabbed two packs from the wall and started talking about the position of the bag on the iliac crest of the hip. I told him that I'm a yoga teacher, and I can at least follow along when it comes to anatomy. He filled the backpacks with pillows and weights to mimic the load I'll be carrying and then taught me how to pick the bag up off the ground, position it on my knee, and swing it over one shoulder to put it on. I followed along, and much to my surprise I didn't fall over. After walking around the store and up and down many flights of stairs, he asked me how it felt. "Good. I think. But I don't know how it's supposed to feel. Are you a backpacker?"

He looked me dead in the eye and said, "Backpacking is my sport." Duly noted. ... Several months ago I bought a one-way ticket to Barcelona, where I'll meet my family over Thanksgiving, followed by a one-way ticket from Florence to Bangalore. I spent hours scouring various websites for the best deals on airfare, but in retrospect that was all fun and games. Now I sit with two-dozen Internet browser windows open, and I research travel insurance and travel safes and underwear that you can keep your passport and credit cards zipped into. I learn about vaccines and Japanese encephalitis. I read other yogis' packing lists, and my favorite suggestion is: "Bring 5 yoga outfits you don't like. In fact, don't bring anything you like to India." For several weeks I've been trying to secure my Indian visa, and a couple nights ago I was on the phone with someone in India again. I called, as usual, around midnight in LA to account for the 13.5-hour time difference and the operating hours of the institute where I'm studying. This time I spoke to three different people, and the last one assured me that I would receive an email with a photocopy of the document I need by today. I'm acutely aware of when the day ends in India, and it ended with no email. When I arrived at the studio to teach a class today, another teacher asked me how I was doing. I made the mistake of telling her the truth, rather than just saying well. By the time my students started arriving I was in tears. Each student offered such kind and thoughtful words and solutions, but it only made me cry more. Fear got the best of me. Waiting on a visa and looking at slash-proof locks isn't as pretty as buying plane tickets. But fear is often just discomfort. There's this thing that happens in yoga postures. The moment of resistance is where the pose actually begins. And often the difference between comfortable and uncomfortable has nothing to do with the pose and has everything to do with you. How you breathe, think, and react. One of my teachers often loudly and assertively guides her students through incredibly difficult postures and transitions, but she ends her directions by saying, "with joy." And so it is with this. I'll breathe and keep calling India and go to a travel clinic and make some purchases on Amazon with joy. Eventually the documents will arrive and I'll be vaccinated and my pack will be organized with everything I need. The teacher who I cried to sent me a message later that said: "Whenever I am full of doubt my mom tells me the story of a village that didn't have rain for the longest time and so one day they gathered everyone and decided to pray for rain. Among the crowd a little boy stood with his umbrella. He believed so much that the moment they ask for rain it will come, that he brought his umbrella with him. So just grab that umbrella and trust that what you ask for will happen, and whatever happens is only the very best for you. I have no doubt everything will fall into place." Instead of an umbrella, I have a backpack. Eventually my pack and I will be in India. For now I'll wait, with joy, for my visa. My home is a disaster. In a moment of panic this weekend I began tearing it apart. Making piles of recycle, garbage, file, shred, Goodwill, keep. And, naturally, minutes after pulling everything from my closet out onto the floor I decided it was a better idea to go to a yoga class.

Today I stared at the piles again, which I now regularly walk through to get to my bathroom and bedroom. I thought about dealing with them, and again I went to a yoga class instead. You could say I'm avoiding packing, but really in these moments I need to be on my yoga mat. And I can't say exactly why. This has plagued me from the very beginning. Almost 10 years ago when I started practicing yoga, something happened. My practice allowed me to move through my life with greater ease. But I didn't understand why bending my knee a certain way and extending my arms and breathing on my mat left me feeling less irritable in traffic and more compassionate to people who don't know how to drive properly. It's what pushed me to enroll in my first teacher training. I so badly wanted to understand why yoga works. I could say in this time of transition that it's comforting and safe. But I also have practices that are frustrating and bring up fears. My yoga mats have seen countless laughs, tears, handstands, face-plants, and extra long savasanas. Those mats have supported me through poses I never imagined practicing and injuries that felt permanent. They've traveled with me on vacations and celebrated New Year's Eve, birthdays, and weddings. Years ago after a painful breakup my friend gave me the option of going out to a bar or a yoga class, and, of course, we ended up on our mats. The bar might have happened later. As a teacher, I also have the honor of witnessing my students' dedication to yoga. Students come to class on their best and worst days. They show up when they get new jobs, when their kids make them crazy, and even when a loved one dies. They come to their mats when they want to and when they have to drag themselves. And they always feel better afterwards. Recently one of my teachers asked me to view my yoga practice as a habit. Is it an addiction? Is it a useful addiction? How do we rely on it without attaching? I don't know. I don't know why we all keep coming back to yoga. And this is what draws me to India. For years I've felt pulled to travel there in the same way that I feel pulled to my mat. Because I want to know WHY. And maybe there won't be an answer. I may come back with more questions than answers. But I want to move closer to the answer, and going to the source of yoga seems like the best way to do that. Going to India seems like the closest I can get. In two weeks someone is moving in to my home, and in a month I'm leaving. Practically speaking, everything is a mess. My passport and Indian Visa are currently at an office in San Francisco awaiting a signed letter from an institute in India, and the rest of my important documents and belongings are scattered all over the floor of my apartment. Meanwhile, I'll probably keep spending the couple hours that I should be packing each day on my yoga mat instead. And I don't know why it will make everything easier, but it will. |

amanda

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed