|

All morning my shoulders have been in my ears. Lifted in that way that protects us evolutionarily by making more space for the kind of shallow breaths required in fight or flight. The problem, though, was that there was no real threat, and I had nothing to run from other than some thoughts.

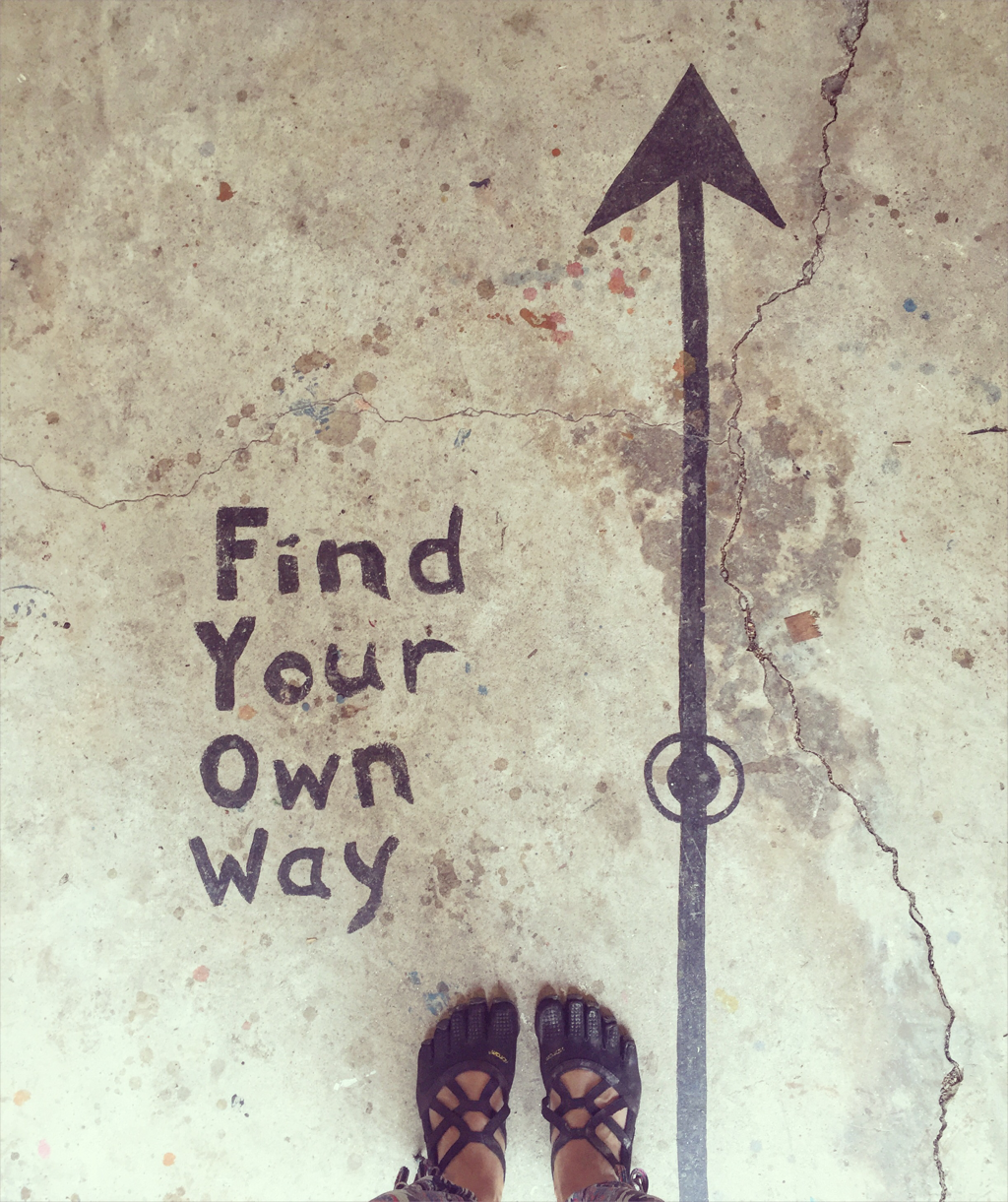

Years ago as a new yoga teacher I regularly themed my classes around reactions. This, to me, has always been one the most obvious and effective benefits of yoga. We make ourselves uncomfortable, and we breathe. And over time it gets a little easier to do the same in the positions we hold in life. To slow down, to soften our shoulders, to breathe into our bellies rather than our collarbones. Paradoxically it also makes it rather noticeable when we fail to find this practice off the mat. Like this morning. All logical thinking told me it was temporary, a momentary stress that is quite simply material and largely unimportant. But that reptilian part of my brain that's hardwired for comfort and safety just kept firing: fear. "Grasp. Hold on. Be afraid." These instincts are protective. They've kept us alive for thousands of years. But they fire at what's available, and without the presence of actual predators and natural disasters, they act on non-life-threatening daily discomforts. A rude coworker, someone driving too slowly, a poorly worded email, the list goes on. I used to have this idea in my mind that over time enough yoga would make us no longer react, floating from situation to situation with a sense of contentment. And perhaps it does eventually. But lately I think the more attainable thing is to free ourselves from our attachment to the reaction itself. It's so easy to either mentally pat ourselves on the back for the "good" calm response or scold ourselves for the "bad" emotional response. However, if we create just a little extra space to pause and observe the response rather than judge it as good or bad, we might find that the response itself both slows down and passes much more quickly. And perhaps over time it does move toward a baseline of contentment or santosha in Sanskrit. A while ago I wrote a little about the koshas or layers of the body. The word kosha can be interpreted as "made of" or "illusion." It's this second word that I found myself discussing at length with yoga retreaters in India. Yoga doesn't teach that this physical world or our bodies or our reactions aren't real. It only calls these things illusions because when our mind becomes fixed on them it isn't free to recognize our true nature. In other words, the more wrapped up you are in your stuff or your regular patterns of thought, the less time you have to reflect on your true self. It's essentially the same as our modern way of reminding one another "in the scheme of things this doesn't really matter" when life's disturbances become stressful or overwhelming. These kinds of teachings often came up as students were getting ready to leave India and go back home. Almost every day the question came up, "how do I bring this practice back to my daily life?" My answer was not unlike what I've already written, and it usually came with many reminders that it's a practice whether you're in India or at home or anywhere, and the best you can do is let go of expectations and be really kind to yourself in the process. Having been through this transition before and now having coached so many other people through it, I didn't think twice about my own departure from India. I arrived at the airport in Goa ready to let go and move on to the next place. It didn't hurt that the next place was Greece and that I was still riding the high of three months of spiritual practice in India. When the gate agent said I'd have to pick up my checked luggage in Turkey before my connecting flight it didn't phase me. She made it sound so simple. Two flights, 20 hours, and no sleep later I arrived in Istanbul having already lost some of my India high. When I found out that I'd have to pay for a visa to enter the country to get my bag it robbed me of my perceived endless bliss, and I broke down in tears. I pleaded my case to at least half a dozen airport employees, certain that there must be another solution, but it turns out that crying does not get your bag transferred to your next flight in Turkey. One visa line and $30 later I found myself in a mass of people wedged between ropes that made switchback lines to only 8 immigration officers. As far as I could tell, I was the only one crying. And not just crying, but sobbing those kind of uncontrollable tears that ramp up the moment you even think of stopping them. A man behind me pushed me any time there was more than 3 inches between me and the next person in line. Eventually he pressed his way alongside me and passed me, and I was too consumed in my own misery to even care. Three young children in front of me weaved their way through legs like a maze. At one point they started fighting, and when the youngest burst into tears I was selfishly grateful to have like-minded company, and I thought, "I get it." All the while I kept thinking about my students in India and about how much time we'd spent talking about emotion, reactions, suffering, non-attachment, and ego. Now here I was less than one day out of India with all of these things in my face. I'd designed entire lectures and discussions around how we bring the lessons of practice and retreat back to our everyday lives, and here I was failing. This, of course, made me cry more. This is also something unique to human emotion. Not only can we experience something like sadness or anger, but we can also then have an emotion about experiencing that emotion. It's that same layer of mental judgment that seeks to label a reaction as good or bad and commends or admonishes ourselves for responding a certain way. We get mad at ourselves for being angry, we feel proud of being happy, we reject our sadness, etc. It's this level of emotion projected onto emotion that is ego and attachment, much more so than the emotion or reaction itself. In any discussion of attachment it's inevitable that the idea comes up of some kind of cold, removed experience of life as the only alternative. But the concept of non-attachment is not that we don't experience emotion; it's that we don't cling to or have an aversion to our emotions. Instead we recognize that they are the human experience, and we simply let them happen. It sounds so simple. When you're happy, be happy. When you're sad, be sad. But how often do we either seek to hold onto an emotion or rid ourselves of one? That seeking, in which we grasp or reject what is, is attachment. As the mass of people continued to shuffle forward toward the passport officers, I continued to cry. But I realized that I didn't need to be more upset about the crying itself. I didn't need to protect my ego from the odd looks, and I didn't need to do anything other than just be sad. Because it's temporary. And because sometimes when you haven't slept, and you just spent the equivalent of three day's budget in India on a visa to enter Turkey for an hour, and you're alone... there's nothing to do but cry. But to cry knowing it's neither good nor bad and that it will pass. It, of course, did. If you ever go to Turkey, know that the light at the end of the immigration control tunnel requires liberal use of your elbows and a whole lot of pushing. At baggage claim it took the help of three more airport employees to find my bag, and thankfully the passport security to leave Turkey thirty minutes later was free of any lines. I even managed to get a tear-free coffee on my way to my last flight. Today with my shoulders still in my ears I took a walk, hoping that if I kept moving my body eventually my mind would follow. That if I neither grasped the stress-filled thoughts nor tried to get rid of them, they would eventually pass. It would make for a really tidy ending to say that my mind is completely clear now, but it would also be a lie. My shoulders are a little lower, and my thoughts? They have a bit more space and a bit less attachment. Practice today, and perhaps a bit more contentment tomorrow.

9 Comments

|

amanda

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed