|

The guesthouse rooftop in Hampi overlooked boulders and ruins. A slightly muffled speaker plays well-known songs in unexpected remixes. The last one was a reggae rendition of "Hello" by Adele. Everyone is seated on the floor on large cushions arranged around tables supported by red plastic Coca-Cola crates. Some people play chess; others read books or type away on their phones. Some nab spaces near the walls to nap.

This is my first experience with backpackers. Mysore was full of yogis. Hampi is full of backpackers. Despite the weeks I've now had with my pack, including the night on a train sleeping on it that it took to get here, I still feel like an outsider. As though it might be treasonous to admit that as happy as I am with the budget accommodations here, I'd also be happy to stay somewhere with western toilets and hot water. Of course, this time in India is intended to be more about experience rather than comfort. And everything is relative. Roughing it to me could be downright luxurious to someone else.

6 Comments

In beautiful Kerala in southern India now, and I happen to have a strong enough internet connection to edit this site. Will attempt to post a bit about the past month this week!

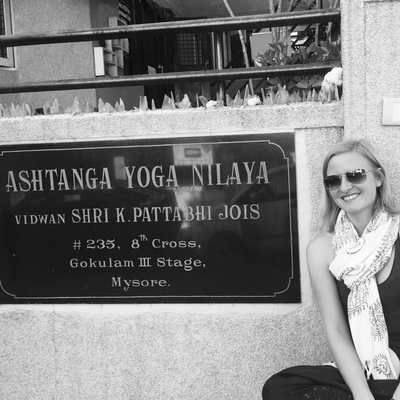

I was introduced to Ashtanga Yoga by Bobbi Boston in Los Angeles, and I was so fortunate to spend my first month in India practicing with Saraswathi at KPJAYI in Mysore. Here's a bit of what daily practice there was like. ... "One more," she yells from inside the shala. "One more. Come!" The window near the staircase is open just enough for the hushed sounds of breath to pass through, punctured by her sharp words. The student at the front of the line enters the shala, and we all shuffle up a step or two. From the outside, this building looks no different from the other homes in the neighborhood. The facade is neutral with brightly colored accents, and rot iron gates and railings wrap around the outside. However, it's the only home on the block with a dozen scooters and bikes parked outside and its own coconut vendor. Some days when the line winds down the staircase and students lean against the walls, it gets noisy with conversations just above a whisper. Together the many murmurs about day trips, the best taxi drivers, and nearby hotel pools are enough to drown out her voice. "Come, one more!" Someone near the window hears the words pass through the sheer white curtain, and soon arms are waving and "one more" is whispered along the line like a game of telephone. When the next student finally startles and presses the door open, there's enough open air for all of us to hear: "Quickly! You talk after!" To an outsider her words might seem aggressive, but it's only her love of the practice that makes the words forceful. Saraswathi was taught by her father, Shri K. Pattabhi Jois, in the lineage of Krishnamacharya, and in India the lineage of a teacher and a practice is of the utmost importance. Jois said that the only people who can't practice Ashtanga Yoga are lazy people, and there is nothing lazy about her teaching. In the shala she commands the space with selflessness, devotion, and humor. Even in her 70's she moves with the strength and grace of someone half her age. She can hold one student's foot in a balancing pose, while also directing another student through the correct breath and movement of a sun salutation. And the next moment she's marching diagonally through the small space between each mat, eyes fixed on a new student, while exclaiming, "bhujadpidasana is not correct!" As yet another student rolls up his mat, she doesn't miss a beat. "One more!" In December, the line was short. Sometimes only few people clutching mats at the top of the stairs meant a five-minute wait. Now the line often reaches the bottom of the staircase, and I stand near the coconut vendor, envying the students who have finished their practice and moved on to drinking coconuts. On these days the wait is an hour. One day I turned to my neighbor and made a comment about how long the line was. Her face lit up, and she said, "I don't mind!" Behind her cheerful, carefree words were so many unsaid things. It was all she had to say to wake me up to my western mind. What's the rush? Do I have somewhere else to be? What's wrong with just standing here and doing nothing? The words "Happy Journey" are everywhere in India. Plastered on billboards at the airport, flashed across electronic signs at tolls on major roads, and printed on bus and train tickets. My Uber driver even said it as I exited his car the other day. I found the words a little cheesy at first. (And if I'm being perfectly honest, I tend to associate "journey" with the TV show The Bachelor, so maybe I'm the cheesy one.) But it is a lovely reminder from India that you better enjoy the process. The quickest way to make yourself miserable here is to rush or focus on the result. Some days just finding a working ATM might take a couple hours, so it's best to make it a pleasant walk along an unfamiliar path or have a chai along the way. Happy journey. And so it is with the line. Far from being an annoyance, it is part of the process. I watch the woman across the street effortlessly draw a beautiful mandala with chalk powder or rice flour outside her front gate. Her 3 children, in school uniforms, race out of the home and jump on a scooter with their father, playfully fighting over who will sit where. The local fruit and vegetable vendors ride their bikes down this dirt road with large trays balanced across the handlebars. These men shout their offerings with elongated vowels. Some days Saraswathi comes outside and shouts her order back over the balcony. She simply nods her head in approval as she watches the vendor weigh each item. Then she disappears back into the ocean of breath, and we all wait to hear her call for one more. We're all assigned practice times when we register. Between 4am and 10am. I thought I had lucked out when I saw 9am written on my student card, but that was before I knew that music from the temple next door to my apartment would wake me up at 5:15am every morning. I know the tune by heart now, and it has quite a lively beat for that hour of the day. It goes on for a half hour of melodic ups and downs. Unfortunately, the quality is what you might imagine playing a radio over the loudspeaker at Target would sound like. It used to alarm me, but now I tend to wake shortly before it begins, and the intro plays in my head in anticipation of the real thing. This, too, is part of the process. What was initially a disturbance, but that I now know I'll miss when I'm gone. Happy journey. Ashtanga Yoga is method that incorporates all 8-limbs of yoga and follows a set sequence of postures for the physical practice. There are led classes, which are similar to yoga classes in the west. But traditionally Ashtanga is taught Mysore-style, named after this very place where it started, in which the sequence is done individually in a room with other practitioners, a teacher, and sometimes assistants. Each student learns the postures at a pace dictated by his or her teacher, and this speaks to the importance of lineage. The practice is never diluted because it is only passed directly from teacher to student. The Ashtanga teacher I first practiced with in LA learned here in Mysore, and so has every other authorized or certified Ashtanga teacher. This sense of tradition has an eclectic mix of students from all over the world standing outside an otherwise typical home in the neighborhood of Gokulam waiting to hear two simple words. Near the shala door, shoes are neatly scattered. Taking off my shoes feels like a ritual. It's when I listen more intently because I like to open the door before she has to call twice. Following her words, the door creaks as I enter, and a puff of humidity presses through the cooler air outside. The breath and movement of three-dozen students heats the room. Saraswathi points toward the newly vacated space, and I assess the best path through the extended limbs and focused gazes. I lay my mat down, and then I make my way to the small changing room. Bags cover the floor, and they are mostly filled with the modest clothes we all wear outside over our leggings and tank tops. When I step onto my mat, the breath comes effortlessly. It's second nature to join; the sound pulls me in like a wave. It has a greater force here than anywhere else I've ever practiced. Perhaps because this is what we're all here for: to practice where the practice started. I get so lost in it one day that I don't hear the words directed at me. "Marichyasana D is wrong," Saraswathi says loudly from across the room. It takes her saying it twice for me to realize that I am, in fact, practicing Marichyasana D. There is magic in the way she says things like this because she manages to convey the importance without judgment. The emphasis behind her words is for the practice to be precise, to be experienced in full. I keep my hands clasped, but turn my head to make eye contact with her. "Straight! Sit up straight," she says with exasperation. She is not impressed by my hunched over twist, and neither is my spine. I adjust myself to sit taller, finding space and length where my lower back has gotten sleepy. It's enough to feel better, and it must look better because she has moved on to the next student, inquiring about which asana she just practiced. I accidentally ended up in my first yoga class in 2006. It was on a beach in Maui, and my dad and my brother ditched me mid-way through. This practice in Mysore is a world away in both location and intention. In some practices here I want to hold on, to remember every little moment because I sense how temporary it is. But after 10 years of practice that has hardly been linear, I try to remind myself that this is part of the process. It matters as much as that first practice and each one in between. A practice that is whole isn't one of perfect poses, but one of waiting and moving and asking questions and being reminded of bad habits and waking up your self. Happy journey. When I finish my practice, I gather my things and cover myself in looser clothing. I tip toe back through the tangled limbs, and my eyes search for Saraswathi to nod in gratitude. Here namaste only means hello, but there are other ways to acknowledge your practice and your teacher. She is busy moving a student's feet behind his head, but not too busy to notice that another student is about to roll up her mat. I catch her attention momentarily as she looks toward the door, and she nods with a quick smile. "One more!" My mom has only subtly asked me when I'll write something, and I have tried. I have a dozen blog posts partially written because every time I start to write about one thing I suddenly want to write something else. So I open a new document, record a new thought, and as soon as I search for more words, I'm lost. It's the same way I felt walking around Mysore when I first arrived. One block is filled with beautiful homes and lush, old trees, and the next is slums with torn plastic tarps for shade. Then the following corner has a traditional restaurant that serves food on banana leafs, and across the street a cow is eating garbage. Another block over is a Domino's Pizza next to a Samsung store. Beggars stand near the bus stops on this main road, and children in school uniforms wait on benches, exchanging stories and laughs. A Mercedes drives by, and a small rickshaw filled with six people lurches over a speed bump and struggles to accelerate. Farther down is the neighborhood sweets shop, which also happens to be right next to the best food cart for churumuri, a favorite local snack of chopped fruits with spices and rice puffs. The smell of earthy spices and frying oil from other stands mixes in the air with exhaust from the nearby traffic. The modern grocery store on that same block is a one-stop shop for everything for flatware to underwear. Outside vendors with fruits and vegetables compete by offering lower prices. They measure the weight in balances, placing the produce on one side and a metal kilogram on the other to determine the correct amount. I have been to places like this before, where the extremes of life are so close together. But each one is unique. And each one wakes you up to all of (for lack of a better word) your shit: what you take for granted, what you avoid, what you attach to. My first week here I barely took any photos. As if my blonde hair and generally confused facial expression weren't enough to make me stand out, pulling out my camera made me feel even more foreign. And my eyes had enough to take in without adding a second lens. Just crossing the street felt like a task. I awkwardly waited, attempting to find the best moment to make it through oncoming rickshaws, scooters, cows, cars, and buses. I often watched dogs successfully cross the street with more grace and ease than I did. Three weeks later I now know that there is never a best moment, but the oddly magical thing is that you always make it across. Yes, drivers honk their horns, and buses don't mind coming within inches of your toes, but there is no perfect timing, so you just go. And everyone is in it together. Which might be the dorkiest thing I could say, but there's something about a little madness that forces you to see other people. Instead of staring at a red light and waiting for it to change, you stare at oncoming traffic and with the right number of beeps and a strange dance of speeding up and slowing down and compromising you figure out a way for everyone make it through. The dogs still look more agile than I do, but my eyes have adjusted. This week on my walk home from the shala someone pulled over and asked me for directions, so my face must look less unsure than it did when I first arrived. To my own surprise I even guided him in the right direction. Mysore has been a lovely little pocket of India to get my feet wet. I've fallen in love with the people, the food, and, of course, the YOGA. Admitting that I struggled with crossing the street here might elicit a laugh from a Mysorian because this is the quiet, calm part of India. Many people call this city a soft landing. At the advice of others students who studied yoga here, I arrived with a hotel booked for 3 nights and planned to spend my first full day wandering around looking for homestays and apartments. I started that morning wary of whether this plan would work, and by evening I had more accommodation options than I knew what to do with. Eventually I'll finish the half-written words about practicing yoga here, taking a Sanskrit class that's held in the women's locker room, the new floors at the shala, riding on a scooter with my 30-pound backpack, visiting a cotton factory, the rickshaw driver who renewed my faith in humanity, and finding a cockroach on my yoga mat. It would be foolish to think that 3 weeks or even 6 months is enough time to really figure anywhere out. I've lived in LA for 6 years, and I still don't have it figured out.

As I roamed around Mysore the other day, my mind still taking everything in, I thought about a quote from Winnie the Pooh. Sophisticated, I know. "Life is miserable," moaned Eeyore. But Pooh just laughed. "Oh, Eeyore! It's your mind that's miserable. Life is just life." I could say that India is beautiful, challenging, chaotic, vibrant, noisy, delicate, mysterious, overwhelming, generous... But India is just India. And my mind is trying to catch up. |

amanda

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed